Another indicator of a good school is its educational trips, residentials and visiting speaker programme. It’s one of the 50 different indicators that feed into the Schoolsmith Score.

There’s a wide range of offers, from the seemingly random Christmas Panto trip, a Year 6 adventure centre overnighter and ‘people who help us’ visitors through to a programme in which each element is an essential and frequent component of a coherent and purposeful curriculum.

This article explains how schools approach trips and speakers, and how they differentiate themselves. Knowing what the average school offers, and what the very best are doing should allow you to judge for yourself whether your target school’s educational trip and visitor programme is good, bad, or indifferent. The article refers to research carried out in Q1 2023 of 3,000 high performing primary schools, state and independent.

Benefits of school trips and residentials

Or, in other words, why does it matter? There’s a fairly uncontroversial body of evidence showing that school trips are a good thing. Google it, and you’ll be hard pressed to find commentary to the contrary.

Oft-cited benefits include bringing a subject alive, putting a subject into an experiential context, reinforcing classroom learning, boosting motivation and improving behaviour, improving self-confidence and broadening horizons.

Residential trips, in particular, are also among the more memorable events of a child’s primary education.

Why are educational trips an indicator of a good education?

It they’re beneficial, then the frequency and relevance of educational trips are a clue to how active and creative a school is being to engage and inspire its pupils.

Over the last five years (2018-23) schools have increased experiential learning throughout their curricula. And, as their curriculum and teaching policies attest, they’re doing it through thematic subject linking, practical subjects and ‘learning outside the classroom’. So, the underlying drivers for increased school trips, residentials and visiting speakers are healthy.

So why are school trips and residentials declining in number?

After the arrest of all excursion activity during lockdown the anecdotal evidence is that trips and residentials have yet to fully recover. And there is some more substantial evidence.

In April 2023 a survey by the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER) on behalf of The Sutton Trust reported that 50% of school leaders had reported cutting school trips, compared to 21% in the 12 months prior.

And in December 2022, research sponsored by Hyundai UK reported that 61% of teachers were less likely to plan trips compared to five years ago.

On the face of it, these findings make sense. Trips cost money, take teacher time to plan, and teaching time to deliver. Over the past five years we’ve had the COVID pandemic, Brexit, school funding issues, teacher recruitment and retention problems, increased paperwork and safeguarding obligations, and to cap it off, an ongoing cost-of-living crisis. Each one presents its own set of obstacles to school trips.

But these are opinion surveys, not records of actual activity.

In the first quarter of 2023 Schoolsmith researched the educational trip provision of 3,000 high performing prep and primary schools. The research suggests that the number of trips is down, compared to five years ago. But not as drastically as the two surveys fear. More significant is the changing nature of educational school trips, day and residential. And it gives us more insight into how schools can differentiate, and how parents can choose between them.

What exactly is an educational school trip or residential?

An educational school trip is one traditionally associated with a curriculum subject. It might be an art gallery for art, a battlefield for history, a riverbank for geography or science, or a synagogue for RS. In recent years, there have been more trips to woodlands or nature reserves as part of an (environmental) science curriculum.

A residential trip involves an overnight stay. Again, they are traditionally associated with geography, science or history field trips. There are also cultural trips, to see the sights and attractions of a major city, in the UK or overseas. But like day trips, outdoor adventure has become more popular. Camping, bushcraft, trekking and outdoor pursuits are connected to the PE curriculum and character development.

These whole-class trips, a particular feature of primary education, exclude sports fixtures and tours, choir or ensemble trips and tours, and other Gifted and Talented trips. The frequency of these trips, for a talented subsection of the cohort, shows no overall change, and are as resilient as ever. They do become an important feature of secondary education when whole-class trips become less relevant.

Who organises school trips?

School staff organise the majority of day or local trips, with input from the venue and the transport company. As such, day trips are more easily adapted to the curriculum.

In contrast, professional operators organise most residential trips, with teachers co-ordinating attendance and ensuring on-location safeguarding. Residentials are therefore more ‘packaged’ by definition.

How much do educational trips cost?

This is one of those length of a piece of string questions. A visit to the local mosque, synagogue, museum, or nature reserve might cost very little. Visits to farms, zoos and theatres might cost a lot more. If there is travel, such as a trip to a town or city, then there is a transport cost too.

Some primary schools guide towards £10 or £20 per term for day trips. I’ve also seen £50-£60. It’s not hard to see how a day trip to London, with transport and entry to a museum or theatre might reach £100. But this wouldn’t be the case every term.

Of course, residential trips cost more. £100 all-in for a day/night at a UK activity centre seems to be the current average. Overseas trips are more expensive, but costs are often managed by accommodation at host schools and travel by coach.

How important are visiting speakers?

In much the same way as school trips enhance the curriculum, so does a school guest speaker programme. The idea is that a visitor with a particular experience or job role comes in to address the pupils and stimulate an activity. It could be an artist, a scientist, a community leader, an athlete, an author, a notable alumnus, or a parent.

A guest speaker visit is logistically easier to manage than a trip and usually cheaper. But at prep and primary schools the school guest speaker programme is underused. After the triumphant visits from fire and police officers, the bloke with the snakes or hawks and the local Centurion, visits tend to peter out from Year 2 or 3. Older year groups might get an annual visit featuring an author or athlete.

Schools who are more serious about visiting speakers have at least one speaker per half term, some weekly or two-weekly. At this frequency speakers specialise by curriculum subject or stimulate debate with a cross-curricular or topical issue.

How many educational day trips should I expect at primary or prep school?

The good news is that all schools offer school trips. They differ, however, in the number, duration and ambition.

The research shows that the average state primary school and independent prep offers one day trip per term for each of Years 1 to 6. The trip might not last a whole day, but it is an educational trip away from the school grounds. Whereas the lowest offer is one trip per year, some offer two every half term.

The average numbers for prep and state schools are surprisingly similar. More significant is the variation by age. Older children have less day trips than younger ones; a trend that continues into senior school.

There is also variation by school locality. Urban schools, with a greater range of cultural attractions on their doorstep, offer more day trips than rural schools. From a lower trip count, rural schools have more woodland or nature-based trips, for example, as part of Forest School.

How many residential school trips should I expect at primary or prep school?

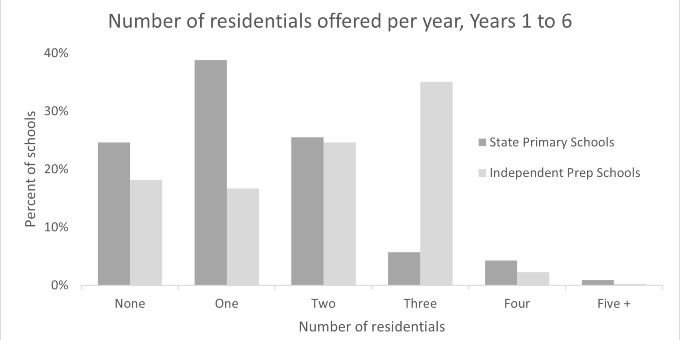

Most state primary schools offer one residential trip per year, the average is 1.3 trips. That trip is typically an outdoor adventure trip in Year 6 and varies between one night and a week in length.

By contrast, and unsurprisingly, most prep schools offer more residential trips. Three is the most common offer, typically for Years 4, 5 and 6, with a median and mean of two trips. Among prep schools there is some variation. Standalone prep schools offer more residentials. Prep schools that teach to age 13 offer fewer to pupils in Year 6 and below. And junior divisions of all-through boarding schools offer the least.

The data also shows that schools in wealthier areas offer more residential trips than those in less wealthy areas. Rural schools offer more residentials than urban schools. And to complete the contrast with day trips, older pupils are more likely to go on a residential than a younger pupil.

How are school trips changing?

School life might be getting back to normal, post-pandemic, but trip activity is down. Not COVID, but price inflation squeezing household budgets and school budgets. The cost-of-living crisis. State schools can only charge for trips and visits that are outside school hours, though they can ask for contributions. Inevitably, day trips and subsidies for poorer pupils on residential trips weigh already tight school budgets. So rather than take that risk, trips are cancelled, shortened or repurposed.

The impact on frequency of day trips has been minimal, according to the Schoolsmith study. What has changed is the distance travelled on those trips, travel costs being a major part of the total cost. Go local is the practice, it seems.

As for residential trips both the frequency, distance and nature have changed. Today 36% of state primaries offer two or more residential trips. In 2018 it was 46%. In addition, trips are more likely to be one or two nights than three, four or five. Overseas trips and hotel accommodation in cultural centres such as London are declining in favour of outdoor adventure centres closer to home and local camping trips.

Private schools usually charge directly for residentials and recoup day trips through school fees. But that’s not to say that that parents haven’t felt the squeeze. The total number of trips has held up over the past five years, and day trips have even increased slightly reflecting the trend towards more outdoor activity. But the durations are down, and the destinations for all but the wealthiest schools are trending towards domestic rather than international locations.

How do schools differentiate on day and residential trips?

Schools still market the number of trips, day and residential, and their visitor programmes as points of differentiation. Perhaps not as crudely as a few years ago. In more prosperous times some prep schools’ brochures would feature geography trips to Iceland, cricket tours to Barbados and rugby tours to South Africa. Though still relevant for senior school pupils, these destinations are less obvious at primary level.

Linking outdoor education to school trips is a more recent phenomenon. Those schools with more coherent outdoor learning programmes move through various stages of Woodland, Forest and Beach School learning through to adventurous trips and camping. Those schools with more residentials are including more camping, starting as a sleepover for Years 1 and 2 on school premises through to hikes in National Parks. They are often packaged as part of a leadership programme, school award, diploma or even baccalaureate.

The very best schools are devising ways to integrate trips, visitors, outdoor learning and the broad curriculum into a coherent programme of learning, rather than a series of discrete, unconnected activities.

School trips in 2028

Expect more primary schools to tie educational trips and speakers more closely to the curriculum. Cost issues will determine the duration and destination of trips, but their frequency will increase. The 32½ hour teaching week, which translates into just over five hours of teaching per day, is already strained by the demands of teaching knowledge, skills, character, and learning habits. Activities that don’t obviously support those areas will fall to the ‘nice-to-have’ wayside.